Introduction

When Sergei Eisenstein died on the 11th of February 1948, a post-mortem examination was conducted to establish the cause of death. His body was subjected to a dissection and his brain was exposed, measured and photographed. The photographs of Eisenstein’s brain were kept by his friend of thirty years, neuropsychologist Alexander Luria, who would show them to his students to illustrate the asymmetry of the brain’s hemispheres. Eisenstein’s brain featured a dramatically enlarged right hemisphere, which is responsible for visual images and spatial information processing, while his left hemisphere was of a normal size.[1] This striking image provides an apt illustration for one of the most challenging and enduring intellectual projects at the intersection of film theory, psychology and philosophy: that of trying to understand how mind, brain and cinema interact. It was also a postscript to Eisenstein and Luria’s scientific collaboration, which at various stages included the linguist Alexander Marr and cultural psychologist Lev Vygotsky. The research program they carried out, from the mid-1920s until Eisenstein’s death, aimed to combine neuroscience, social sciences, and cinema theory to address the neural basis and semiotics of screen aesthetics.

This collaboration reveals and confirms Eisenstein’s status as a theoretician with broad interdisciplinary interests, as has been increasingly acknowledged in the scholarly literature.[2] As Francesco Casetti notes: “In Eisenstein we find a constant urge to operate in the interstices of different sciences, between linguistics and anthropology, between psychology and aesthetics, between the history of art and biology.”[3] While some aspects of Eisenstein’s theoretical activity – such as his engagement with linguistics and anthropology [4] – have been explored more extensively, his extensive engagement with the emerging discipline of psychology in the first half of the 20th century remains underestimated.

Leer más…

La escritora y activista feminista Silvia Federici estudió la cacería de brujas como un periodo fundamental para el advenimiento del capitalismo y el establecimiento del control del Estado sobre el cuerpo de las mujeres para asegurar y disciplinar el trabajo reproductivo. Cualquier práctica o saber ajeno a esta lógica de división sexual de trabajo era señalado de brujería y castigado severamente. Se trata de un estudio sumamente importante para entender la relación entre la acumulación del capital y el control sobre el cuerpo de las mujeres, aún en nuestros días.

La escritora y activista feminista Silvia Federici estudió la cacería de brujas como un periodo fundamental para el advenimiento del capitalismo y el establecimiento del control del Estado sobre el cuerpo de las mujeres para asegurar y disciplinar el trabajo reproductivo. Cualquier práctica o saber ajeno a esta lógica de división sexual de trabajo era señalado de brujería y castigado severamente. Se trata de un estudio sumamente importante para entender la relación entre la acumulación del capital y el control sobre el cuerpo de las mujeres, aún en nuestros días.

Teoría marxista de la cultura, la ideología y la hegemonía.

Teoría marxista de la cultura, la ideología y la hegemonía.

The reissue of this book, first published in 1983, by a feminist with long involvement in the US civil rights and women’s movements, is the sign of renewed interest in ideas of socialism and feminism for a new generation. It is also a sign of the desire for an analysis of feminism which links women’s oppression to its material roots and tries to locate it in wider society. Vogel succeeds in giving us an over view of Marx’s theory in relation to women, and puts forward her analysis of where women’s oppression is located. She has become one of the leading advocates of what is termed ‘social reproduction theory’, which explains that oppression in women’s role in the reproduction of labour power.

The reissue of this book, first published in 1983, by a feminist with long involvement in the US civil rights and women’s movements, is the sign of renewed interest in ideas of socialism and feminism for a new generation. It is also a sign of the desire for an analysis of feminism which links women’s oppression to its material roots and tries to locate it in wider society. Vogel succeeds in giving us an over view of Marx’s theory in relation to women, and puts forward her analysis of where women’s oppression is located. She has become one of the leading advocates of what is termed ‘social reproduction theory’, which explains that oppression in women’s role in the reproduction of labour power.

Manuel Sacristán. Translated and edited by Renzo Llorente

Manuel Sacristán. Translated and edited by Renzo Llorente “La cruda contemplación de la gran convulsión de los intereses

“La cruda contemplación de la gran convulsión de los intereses A continuación presentamos la introducción del libro Para qué sirve El Capital: un balance contemporáneo de la obra principal de Karl Marx, publicado por

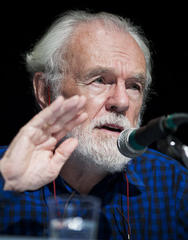

A continuación presentamos la introducción del libro Para qué sirve El Capital: un balance contemporáneo de la obra principal de Karl Marx, publicado por  DAVID HARVEY

DAVID HARVEY  Neil Davidson, in an excerpt from his new book, defends Walter Benjamin from sectarian dismissals and academic obscurantism.

Neil Davidson, in an excerpt from his new book, defends Walter Benjamin from sectarian dismissals and academic obscurantism. Iván Padilla

Iván Padilla

En este programa temático de

En este programa temático de