The objective of the following observations is to offer a rough overview of central ways of reading Marx’s theory. These are to be presented – by means of a few selected topics – as Marxisms that can be relatively clearly delimited from one another, and the history of their reception and influence will be evaluated with regard to the common-sense understanding of “Marxist theory.”

The objective of the following observations is to offer a rough overview of central ways of reading Marx’s theory. These are to be presented – by means of a few selected topics – as Marxisms that can be relatively clearly delimited from one another, and the history of their reception and influence will be evaluated with regard to the common-sense understanding of “Marxist theory.”

A distinction will be made between the hitherto predominant interpretation of Marx, primarily associated with political parties (traditional Marxism, Marxism in the singular, if you will), and the dissident, critical forms of reception of Marx (Marxisms in the plural), with their respective claims of a “return to Marx.” The first interpretation is understood as a product and process of a restricted reading of Marx, in part emerging from the “exoteric” layer of Marx’s work, which updates traditional paradigms in political economy, the theory of history, and philosophy. Systematized and elevated to a doctrine by Engels, Kautsky, et al, it succumbs to the mystifications of the capitalist mode of production and culminates in the apologetic science of Marxism-Leninism. The other two interpretations, specifically Western Marxism as well as the German neue Marx-Lektüre (“new reading of Marx”), usually explore the “esoteric” content of Marx’s critique and analysis of society, often consummated outside of institutionalized, cumulative research programs, by isolated actors in the style of an “underground Marxism.”

In order to characterize both ways of reading, some strongly truncated theses, limited to a few aspects, must suffice. In particular the ambitious proposition, first formulated by Karl Korsch, of an “application of the materialist conception of history to the materialist conception of history itself” – one that goes beyond the mere presentation of intellectual history, towards an immanent theoretical critique that critically considers the connection between historical forms of praxis and theoretical formations of Marxism – cannot be carried out here. In addition, a consideration of those readings which are critical of Marx or Marxism can also be disregarded here, insofar as their picture of Marx usually corresponds to that of traditional Marxism.

I therefore begin with the hegemonic interpretative model of traditional Marxism, and only at the end of my presentation will I conclude with a few positive determinations of what I regard as the fundamental systematic intention of Marx’s work. I do this primarily because a differentiated reading of Marx’s work can only be gained in the course of the learning processes of Western Marxism and the neue Marx-Lektüre. Leer más…

Replying, in the Postface to the second edition of Capital, to the accusation of Hegelianism leveled at him by critics of his publication, Marx insisted that his “dialectical method is, in its foundations, not only different from the Hegelian, but the exact opposite of it.” At the same time he avowed himself “the pupil of that mighty thinker,” acknowledging that he had “even, here and there in the chapter on the theory of value, coquetted with the mode of expression peculiar to him” (Marx 1976a, 102-3). It is evident that this verbal coquetry cannot be the measure of Marx’s pupilship. To begin with, his initial writings are largely dominated by a determined struggle with Hegelian idealism. And, more to our point, his engagement in the project of a critique of political economy in 1857 involved a second phase of attention to Hegel, with a new appreciation of the “mighty thinker.”

Replying, in the Postface to the second edition of Capital, to the accusation of Hegelianism leveled at him by critics of his publication, Marx insisted that his “dialectical method is, in its foundations, not only different from the Hegelian, but the exact opposite of it.” At the same time he avowed himself “the pupil of that mighty thinker,” acknowledging that he had “even, here and there in the chapter on the theory of value, coquetted with the mode of expression peculiar to him” (Marx 1976a, 102-3). It is evident that this verbal coquetry cannot be the measure of Marx’s pupilship. To begin with, his initial writings are largely dominated by a determined struggle with Hegelian idealism. And, more to our point, his engagement in the project of a critique of political economy in 1857 involved a second phase of attention to Hegel, with a new appreciation of the “mighty thinker.”  El pasado 14 de enero murió la historiadora, politóloga y filósofa marxista Ellen Meiksins Wood, una de las personalidades intelectualmente más fértiles y sólidas del pensamiento socialista de las últimas décadas. Nació en Nueva York (1942), en el seno de una familia de emigrantes judío-letones en la tradición socialista del

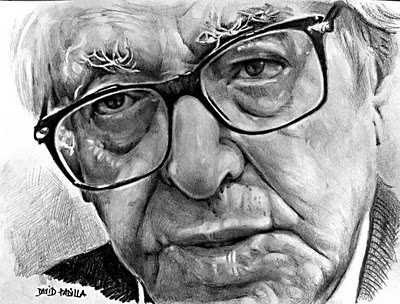

El pasado 14 de enero murió la historiadora, politóloga y filósofa marxista Ellen Meiksins Wood, una de las personalidades intelectualmente más fértiles y sólidas del pensamiento socialista de las últimas décadas. Nació en Nueva York (1942), en el seno de una familia de emigrantes judío-letones en la tradición socialista del  El contexto es el de la dictadura franquista. Sacristán nace en 1925, dentro de una dictadura, la de Primo de Rivera. A sus seis años llega la República, el gran acontecimiento de renovación cultural y política de España. Pero la renovación da un vuelco en 1936, con el estallido de la Guerra Civil, cuando Sacristán tiene 11 años. La victoria de los militares golpistas, cuando Sacristán ha cumplido 14 años, significa que vuelve la dictadura, esta vez sobre una España en escombros, los producidos por tres años de terrible guerra civil. En este contexto de país en ruinas, dominado por militares, eclesiásticos y falangistas, termina su bachillerato, y, como a tantos españoles de su generación, le tocará vivir la dictadura de Franco durante 40 años. Sólo podrá vivir nueve años de posfranquismo, que tampoco le trató muy bien, ya que la conferencia de rectores de universidad se negó a concederle una cátedra en 1980. Sacristán llegó a catedrático en 1984, un año antes de su muerte.

El contexto es el de la dictadura franquista. Sacristán nace en 1925, dentro de una dictadura, la de Primo de Rivera. A sus seis años llega la República, el gran acontecimiento de renovación cultural y política de España. Pero la renovación da un vuelco en 1936, con el estallido de la Guerra Civil, cuando Sacristán tiene 11 años. La victoria de los militares golpistas, cuando Sacristán ha cumplido 14 años, significa que vuelve la dictadura, esta vez sobre una España en escombros, los producidos por tres años de terrible guerra civil. En este contexto de país en ruinas, dominado por militares, eclesiásticos y falangistas, termina su bachillerato, y, como a tantos españoles de su generación, le tocará vivir la dictadura de Franco durante 40 años. Sólo podrá vivir nueve años de posfranquismo, que tampoco le trató muy bien, ya que la conferencia de rectores de universidad se negó a concederle una cátedra en 1980. Sacristán llegó a catedrático en 1984, un año antes de su muerte. Erik Olin Wright on class, socialism, and the meaning of Marxism

Erik Olin Wright on class, socialism, and the meaning of Marxism En el programa más reciente de

En el programa más reciente de  Intervención de Adolfo Sánchez Vázquez en el Congreso «Materialismo histórico y teoría crítica» desarrollado en septiembre de 2002 en la UCM.

Intervención de Adolfo Sánchez Vázquez en el Congreso «Materialismo histórico y teoría crítica» desarrollado en septiembre de 2002 en la UCM.  Presentamos la conferencia de la Dra. Frigga Haug, especialista en la obra de Rosa Luxemburg y quien nos presenta un acercamiento desde el feminismo a la obra de dicha autora. El acercamiento propuesto involucra directamente la concepción de la política de la autora polaca».

Presentamos la conferencia de la Dra. Frigga Haug, especialista en la obra de Rosa Luxemburg y quien nos presenta un acercamiento desde el feminismo a la obra de dicha autora. El acercamiento propuesto involucra directamente la concepción de la política de la autora polaca».  En un artículo para The Prime Russian Maganize (en su edición sobre el Marxismo), el poeta Alexei Tsvetkov escribió este retrato de Évald Iliénkov, el último Marxista Soviético y una de los más grandes y originales pensadores de la Unión Soviética. Tsvetkov nos ofrece un retrato de una figura realmente única cuyas obras merecen ser releídas y traducidas, pero también un retrato poco habitual de los tiempos y la atmósfera en la que vivió.

En un artículo para The Prime Russian Maganize (en su edición sobre el Marxismo), el poeta Alexei Tsvetkov escribió este retrato de Évald Iliénkov, el último Marxista Soviético y una de los más grandes y originales pensadores de la Unión Soviética. Tsvetkov nos ofrece un retrato de una figura realmente única cuyas obras merecen ser releídas y traducidas, pero también un retrato poco habitual de los tiempos y la atmósfera en la que vivió.

El día de hoy gracias al apoyo del Dr. José Gandarilla tenemos el privilegio de poder presentar la reciente presentación que se hizo a la nueva edición de las «16 Tesis de Economía Política» obra capital en el pensamiento del Dr. Enrique Dussel.

El día de hoy gracias al apoyo del Dr. José Gandarilla tenemos el privilegio de poder presentar la reciente presentación que se hizo a la nueva edición de las «16 Tesis de Economía Política» obra capital en el pensamiento del Dr. Enrique Dussel.